Climate readiness isn’t about politics; it’s about pragmatism. The market doesn’t care about your ideology; it cares whether you’re prepared to adapt, compete, and thrive in a world reshaped by environmental realities.

Environmental uncertainty has become the rule rather than the exception. Traditional business models, built on outdated assumptions, are crumbling under the weight of climate risks that can no longer be ignored. For decades, organizations have treated these risks as peripheral issues to be addressed later or, better yet, by someone else. That era is over.

Companies must embrace climate readiness as a core operational strategy to thrive in this rapidly changing landscape. This isn’t about corporate responsibility or greenwashing; it’s about survival, relevance, and securing a competitive edge in a marketplace transforming faster than most leaders realize.

From Risk to Reality

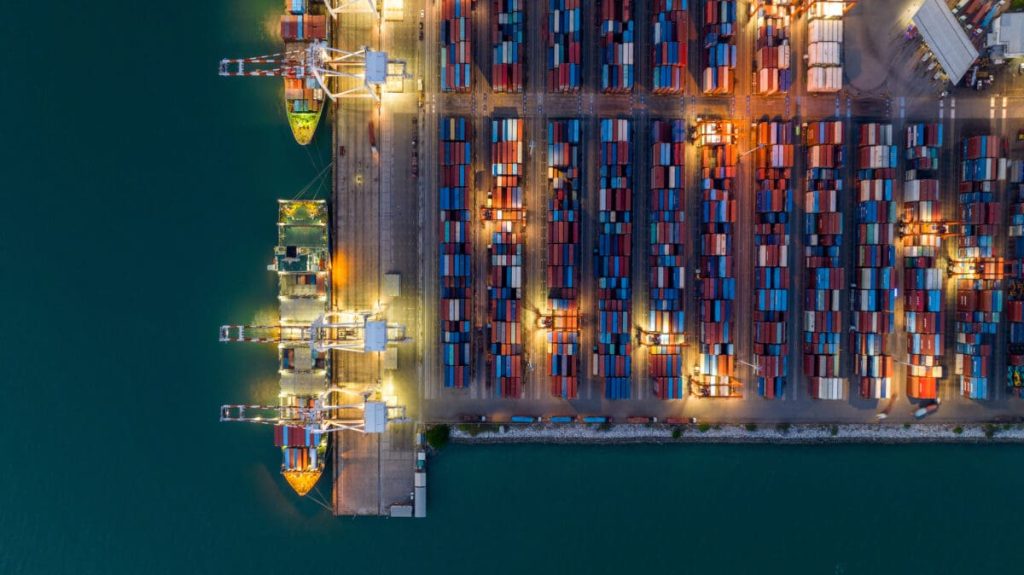

The global economy has reached a tipping point. Wildfires, floods, and supply chain disruptions are no longer hypothetical risks confined to academic reports. They are active threats, costing billions annually and reshaping entire industries in real-time. Yet many businesses remain reactive, treating climate challenges as temporary inconveniences rather than the systemic shifts they represent.

Consider the energy sector. Companies that once banked on the slow decline of fossil fuels are now racing to diversify portfolios as demand for renewable energy skyrockets. Similarly, agriculture faces existential challenges as shifting weather patterns disrupt crop yields, forcing a reevaluation of longstanding production models.

This is not a phase; it’s the new normal.

The Fatal Flaw in Legacy Thinking

The failure to integrate climate readiness stems from clinging to outdated success metrics. Quarterly earnings reports and shareholder appeasement dominate decision-making, leaving little room for long-term strategies to address environmental vulnerabilities.

Companies operating under “business as usual” frameworks effectively build castles on sand. For every organization ignoring climate risks today, there’s a disruptor preparing to seize market share by offering sustainable, resilient alternatives.

Climate readiness isn’t just a defensive strategy; it’s a catalyst for innovation and growth. Forward-thinking businesses understand that embedding climate strategies can unlock new markets, attract investment, and future-proof operations against uncertainty.

What Does Climate Readiness Look Like?

- Embedding Resilience into Strategy: Resilience must extend beyond supply chain management and into the DNA of business planning. Flexible systems capable of adapting to resource shortages, volatile markets, and shifting regulations are essential.

- Investing in Green Technology: Transitioning to low-carbon technologies is no longer optional. Companies that delay risk being outpaced by competitors leveraging advancements in energy efficiency, carbon capture, and sustainable production.

- Rethinking Talent and Leadership: Climate readiness requires leaders who understand the complexity of these challenges. Organizations must prioritize hiring individuals who think beyond profit margins to consider broader environmental and social impacts.

- Transparency as a Differentiator: Consumers, investors, and regulators demand greater accountability. Companies that demonstrate measurable progress on climate goals earn trust and secure long-term loyalty in ways greenwashing never will.

- Developing Cultural Competency for Global Climate Challenges: Climate solutions must work within diverse cultural, regional, and economic contexts. Business programs should emphasize cultural competency, teaching students to navigate differences in governance, societal values, and environmental priorities across geographies. This skill ensures that climate strategies are inclusive, effective, and respectful of local needs, enabling leaders to drive meaningful global impact.

The Educational Gap: Why Business Schools Aren’t Producing Climate-Ready Leaders

One of the most significant barriers to achieving climate readiness is a glaring gap in our education system, particularly in business programs. While industries face mounting climate challenges, most Bachelor of Science (BS) and Master of Business Administration (MBA) programs remain in outdated frameworks.

These programs excel at teaching profitability, market dynamics, and operational efficiency, yet they fail to equip future leaders with the tools to navigate the complexities of a climate-impacted economy. This disconnect isn’t just a missed opportunity; it’s a systemic flaw.

The Problem: Outdated Curricula for a New Era

Business education revolves around traditional pillars like competitive strategy, financial modeling, and global trade. Discussions of sustainability, when included, are often relegated to electives or niche specializations.

Even when environmental issues are addressed, they are typically framed through narrow lenses like corporate social responsibility (CSR) or isolated green initiatives rather than as integral to core business strategy.

The result? Graduates excel at quarterly planning but are ill-equipped to address supply chain disruptions, regulatory shifts, or the long-term financial impacts of climate change.

The Demand for Climate-Ready Education

The absence of comprehensive climate-focused business programs isn’t just an academic shortcoming; it’s a market failure. Employers are increasingly desperate for leaders to understand the interplay between business strategy and environmental sustainability.

A 2023 Deloitte survey revealed that while 60% of executives view climate-related risks as critical, only 15% feel their organizations are prepared to address them. This gap underscores the urgent need for business schools to evolve.

What Should Climate-Ready Business Education Look Like?

- Integrating Climate Risks into Core Courses: Courses like finance, operations, and strategy must include case studies on adapting to extreme weather, resource scarcity, and evolving consumer expectations.

- Real-World, Interdisciplinary Learning: Climate challenges cross boundaries, and so should education. Programs should emphasize collaboration across environmental science, engineering, and public policy.

- Training for Ethical Decision-Making: Leaders must be prepared to balance profitability with environmental stewardship. This involves tackling ethical and strategic trade-offs in transitioning to sustainable business models.

- Emphasizing Measurement and Accountability: Future leaders must be fluent in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) principles and familiar with established frameworks like the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and Science-Based Targets (SBTi). These tools are becoming as essential as financial modeling, offering benchmarks to effectively track and communicate progress toward sustainability goals.

However, without universally established standards in specific sectors or geographies, leaders must be able to create bespoke measurement systems tailored to their organization’s unique challenges and opportunities. Designing your metrics requires balancing rigor with relevance, ensuring they are actionable, transparent, and aligned with overarching climate objectives.

The ability to measure and account for climate-related impacts is no longer a “nice to have.” It is a critical skill that underpins credibility with investors, builds trust with stakeholders, and drives meaningful transformation.

The BS & MBA That Lead to Irrelevance

The lack of a climate focus in BS and MBA programs is particularly concerning. These programs, traditionally the breeding ground for C-suite leaders, risk producing graduates unprepared for the modern economy’s defining challenges.

Imagine a BS or MBA graduate managing supply chain disruptions caused by climate-related events. Without training in adaptive strategies or climate finance, they’ll rely on generic management principles with little practical value. This isn’t hypothetical; it’s already happening across industries. To remain relevant, business programs must prioritize climate readiness as a cornerstone of leadership development.

Examples of How Ignoring Climate Readiness Manifests:

- Car Dealerships Unable to Sell EVs:

As electric vehicles (EVs) dominate the market, dealerships that fail to train their sales teams on EV technology, charging infrastructure, and government incentives will lose customers to competitors who can confidently address these concerns. Selling an EV is not the same as selling a gas-powered car; it requires expertise and trust, which outdated sales approaches cannot provide. - Insurance Companies with Outdated Risk Models:

Climate-driven disasters reshape risk landscapes, yet many insurance companies rely on historical data and outdated models. Without training their risk adjusters to incorporate real-time climate data and evolving patterns, insurers will face significant losses or price themselves out of the market with premiums that fail to reflect actual risks. - Retailers Unable to Adapt Supply Chains:

Retailers relying on “business as usual” supply chain strategies are vulnerable to climate disruptions like floods, droughts, or extreme weather. Without leaders skilled in resilience planning, organizations will struggle to maintain inventory, alienating customers and eroding market share. Competitors with climate-informed logistics systems will step in to fill the gap. - Agricultural Firms Losing to Sustainable Competitors:

As consumers demand more transparency and sustainability in food production, agricultural firms that don’t adopt climate-resilient practices like water-efficient irrigation or carbon-neutral farming risk losing contracts with large buyers like grocery chains or restaurants. Firms unable to meet sustainability standards will be left behind in demanding market action. - Marketing and Advertising Firms Missing the Sustainability Message:

As consumers increasingly prioritize sustainability, marketing and advertising firms that lack the expertise to craft authentic, climate-conscious campaigns will lose clients to agencies that can. Brands seek partners who understand how to communicate environmental responsibility without falling into greenwashing traps. Firms cannot navigate this delicate balance risk, which is their reputation and that of their clients. This leads to lost contracts and diminished credibility in a rapidly shifting market.

These examples demonstrate that climate readiness is not a theoretical exercise; it’s a make-or-break issue for industries worldwide. Organizations that fail to prepare will be disrupted, displaced, and left behind.

Closing the Gap

If business schools fail to improve, the consequences will ripple far beyond academia. Companies will struggle to find climate-literate leaders, investors will grow wary of ill-prepared organizations, and industries will miss critical innovation opportunities; the responsibility to demand better lies with educators and the broader business community.

The modern consumer demands purpose, accountability, and action more than products or services. Leaders equipped with the skills to integrate climate strategies, measure impact, and navigate global challenges are no longer optional; they are essential. If your organization is to thrive in this new era, you must prioritize these competencies now. Whether through hiring climate-ready talent, upskilling your current leadership, or risk falling behind, one thing is clear:

The cost of inaction will far outweigh the investment in readiness. The question is no longer if these changes are necessary but whether you’re prepared to lead or destined to follow.

A Call to Action for Business Leaders

The time for incrementalism is over. Climate readiness demands bold action and a willingness to challenge entrenched thinking. Leaders must ask themselves:

- Are we building businesses that will survive the next quarter-century or just the next quarter?

- Are we leading the charge toward sustainability or waiting for competitors to define the path?

- Are we treating climate strategy as an optional add-on or the engine of our long-term success?

- Are we hiring climate-ready graduates who can hit the ground running?

Simply put, the businesses that thrive in the coming decades will treat climate readiness as the standard, not the exception. Business as usual is over. What comes next is up to you.

Learn more about the sustainable business programs at Unity Environmental University and start building a resilient future today.

Written by Dr. Melik Peter Khoury, President of Unity Environmental University and Professor of Sustainable Enterprises