A Spotlight on Unity Alum Dr. Mark Alter, Class of ’69

Before his name became synonymous with inclusive education policy, Dr. Mark Alter was part of something much smaller: Unity’s very first class of students.

He would go on to advise governments, lead international research, teach thousands of teachers, and shape how entire educational systems can and should support the students who need them the most. But long before New York University (NYU), the Fulbright Senior Specialist award, and decades of influence, Alter was a young man stepping off a plane into a state he’d never been to, looking for something different. The country was in upheaval. He had heard of an experimental, still unaccredited college in Maine.

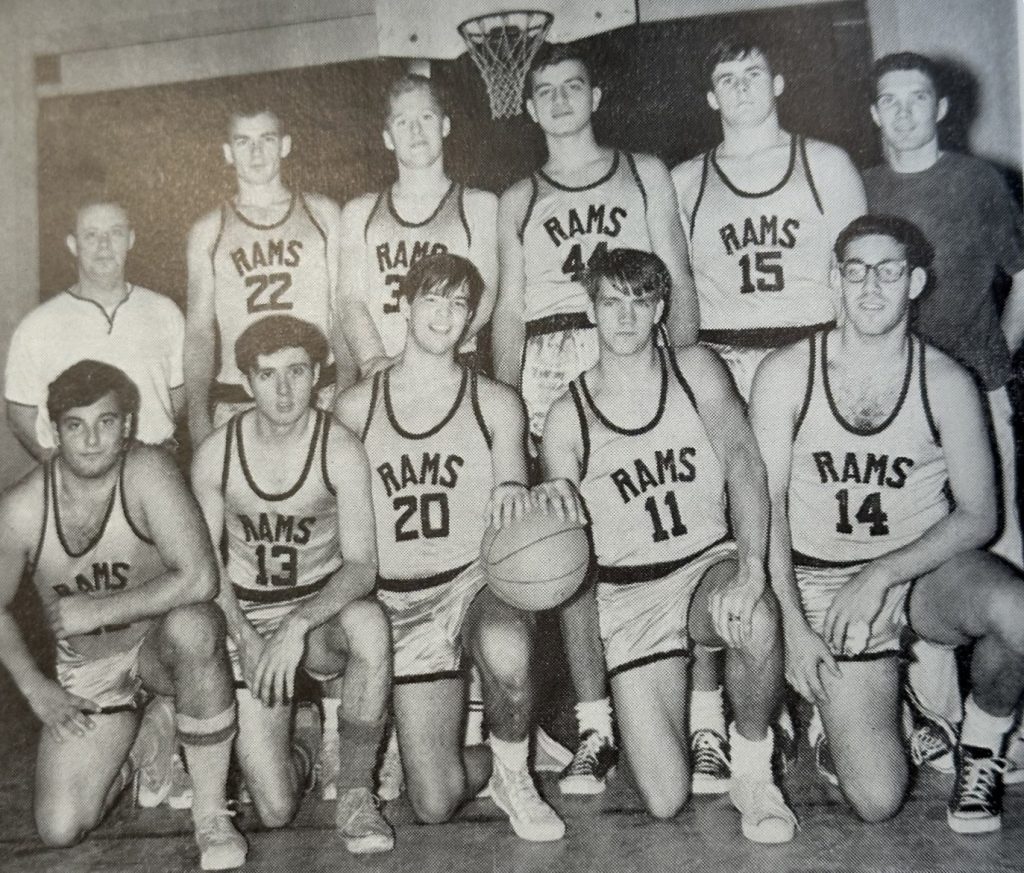

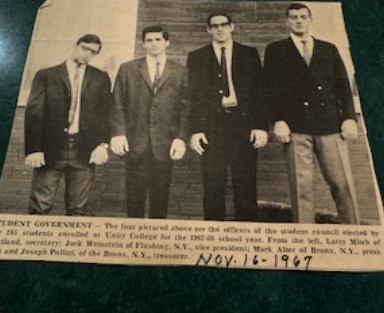

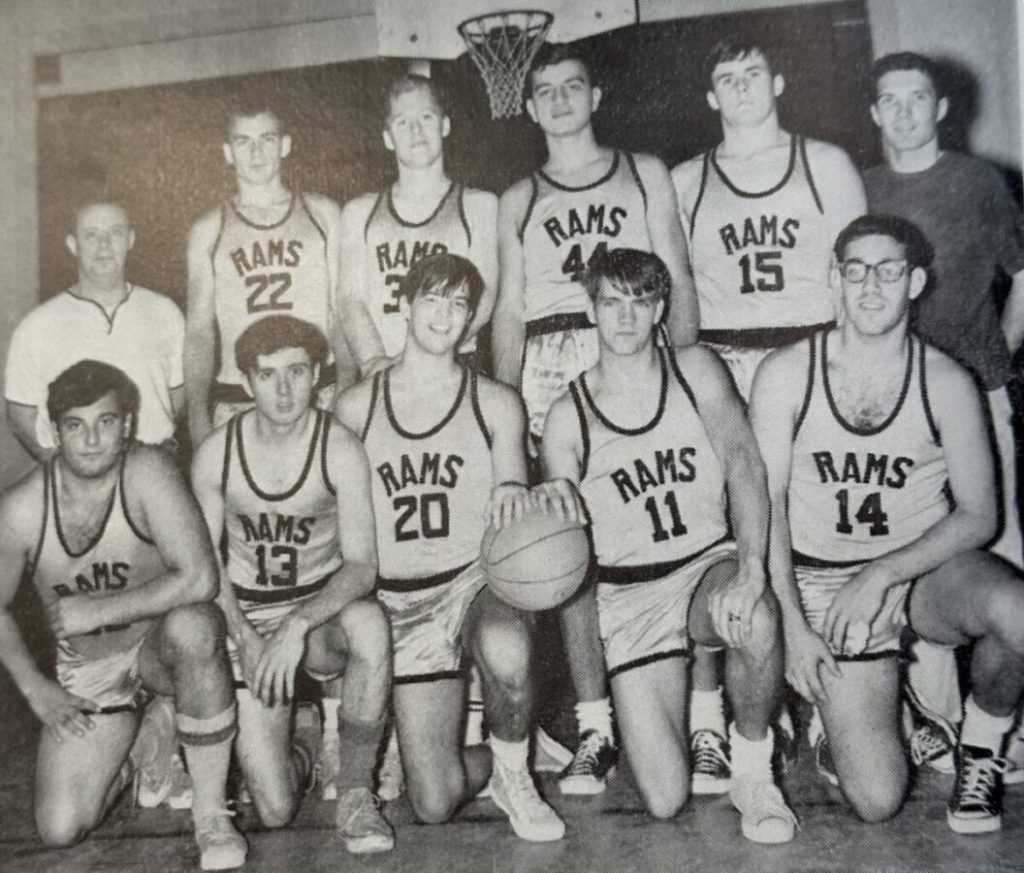

(Photos courtesy of Dr. Mark Alter. The photo on the left is of Unity’s first basketball team with Alter wearing #14.

The photo on the right is of Unity’s Student Government with Alter standing second from the right.)

Unity Institute was small. Unproven. And, at times, precarious. There were fewer than two dozen students. Faculty sometimes went unpaid. Classes took place where the students were, in kitchens, on porches, in borrowed spaces around town. “We were surviving together,” Alter recalls. “Fighting for something none of us could quite name at the time, but we knew it mattered.”

That formative experience, messy, alive, human, would shape the rest of his life.

Alter went on to become a professor at the NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development. He has trained educators across the globe, from New York to Romania, and played a critical role in expanding the reach and definition of inclusive education. He was a graduate student when the landmark Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was passed in 1975 and was directly involved in the seminal Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Citizens court case, one of the cases that laid the groundwork for that legislation. He has authored or co-authored more than a dozen books, edited academic journals, served on review panels for the U.S. Department of Education, and remains one of the field’s most cited scholars.

(Photo courtesy of Dr. Mark Alter. The above image shows Alter on the right and his wife Amy on the left.)

His life’s work centers around an idea that some would argue is an ideal: heterogeneity. Education that is as variable and flexible as the humans trying to access it.

“You build around the learner that’s what the law said in 1975,” Alter says. “There’s more to teaching than curriculum. How do you build a democratic environment that’s student centered?”

That same question has guided Unity through the past decade, as the institution reinvented itself for the twenty-first century. Beginning in 2016, Unity pivoted to include an online model. Today, about 95 percent of courses are offered remotely, and enrollment has soared by more than 1,400 percent, from roughly 600 students to more than 9,100.

When Unity began expanding into new formats, offering both in-person and distance education designed to meet students wherever they are, Alter was, at first, unsure. The Unity he remembered had been hyperlocal, deeply embodied, visceral. What would that experience look like for students not sharing the same snowfall?

“It didn’t look like the Unity I knew,” he says. “But the newer model, while it is a different model I think it probably saved Unity, and, if there is no college, there is no pedagogy.”

With time, Alter began to see the shift through the same lens that has guided his entire career. Diversity in learning, how it looks and is accessed, is something to design for, with the student at the center.

“My daughter received her nursing degree from NYU. She decided to go for her master’s, but she was working 12-hour shifts and had a family. She did it online and it was great for her. The flexibility enabled her to do it.”

Unity’s redesign has gone hand-in-hand with an affordability pledge: undergraduate online tuition has been frozen at $470 per credit since 2018 and is guaranteed not to rise until at least 2030. At the same time, the university recently raised its minimum full-time salary to $50,000 and delivered an average 7 percent raise to all employees, proof that scaling access can support both learners and the people who serve them.

More than 50 years after graduating, Alter sees a familiar instinct at Unity: an impulse to build an education that meets people where they are in life, not just in a classroom. First-generation students. Working adults. Parents. People in motion.

“Have things changed? Yes. Is it better or worse? That’s not the right question. It’s different. What Unity is doing now features more demanding academic coursework and expanded curricular offerings than what came before.”

If his life’s work has a thesis, it’s that time and space gives room for the perspective of optimism. That heterogeneity is not something to fix, it’s something to build upon. Whether in classrooms or institutions, the goal is the same: create spaces that allow people to exist, learn, and grow in their full complexity.

Now, in the midst of his fifth decade at NYU, Alter remains deeply involved in preparing the next generation of educators. He lectures globally, mentors doctoral students, and continues to push for a future in which access is not a privilege, but a principle. On campus, his students speak of him with deep respect and thoughtful affection. A recent post from NYU’s Teaching & Learning Instagram features a photo of him sitting in a semi-circle of students, his face turned away from the camera as he smiles at the faces looking back at him. The caption mentions the course he was teaching at the time and simply adds, “In this course, [Professor Alter] invites multiple guests and students learn how to help students with multiple disabilities to enjoy their quality of life.”

When asked what keeps him hopeful, in today’s world of higher education turbulence, after all these years and all these systems, his answer is simple: “Humanity. Teaching is not an episodic event. We are resilient. We have grit. We keep trying.”

Learning that works for everyone doesn’t come easily. It comes from people who keep pushing, who stay hopeful, who insist that the path forward can be focused on meeting people where they are in life, in ability, and in the world.

Alter graduated from Unity with a BA in Psychology. In 2007, he was awarded the NYU Distinguished Teaching award. Alter and his wife, Amy have three children and eight grandchildren.