How to Write a Strong Introduction

Ask the Following Questions

You will rely on previous studies to build the foundation for your project. It is important to understand how your project fits into the existing body of knowledge.

- What do we know about the topic?

- What open questions and knowledge do we not yet know?

- Why is this information important?

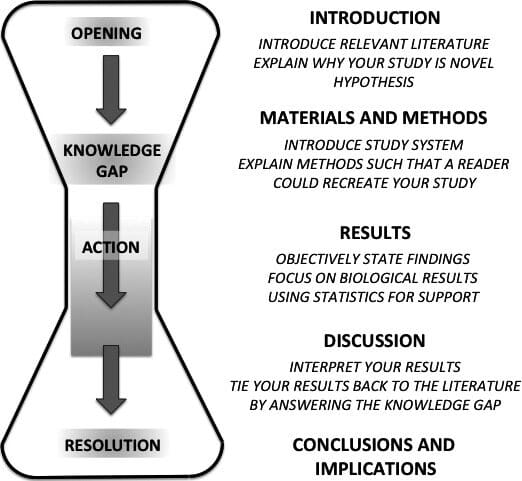

This will provide valuable insight into what is known and help you to successfully craft a compelling story. If possible, note what sets your research apart from the current published literature. In the figure below, an hourglass shape is used to represent the breadth of information for the entire paper writing process. However, in the introduction the breadth of information goes from broad to narrow, or funnel shaped. Oftentimes, you will hear this described as the “Funnel Method” of writing an introduction.

When organizing your introduction, start with the broadest, most encompassing information. Then move to information that is specific to your topic. Your introduction should end with information directly related to your project and finally, your project thesis/hypothesis.

When beginning your introduction start with an outline similar to the following:

- Relevant Background

- Broadest context – What is known about the issue? What isn’t known?

- Intermediate context – What are the implications or societal impacts of the issue?

- Directly relevant context – Who is the partner and how are they impacted by the issue?

- What is your project and how does it address the issue for your partner?

Introduction TIPS

-

Noting a Citation

Instead of writing like this…. Kilner et al. (2004) found that cowbird nestlings use host offspring to procure more food.

Avoid focusing the sentence on the study and the author, instead focusing on the relevant information, not … A study on cowbirds in New York conducted by Dr. Rebecca Kilner and colleagues found that …

Instead, use an in-text citation… Cowbird nestlings use host offspring to procure more food. (Kilner et al. 2004)Do not directly quote sources unless the statement is famous or cannot be stated in any other words. Always paraphrase the relevant information in the source while respecting the context in which the information was presented.

-

Presenting findings

Do not parrot everything you find, instead synthesize, compare, and contrast findings. Paragraphs should not be built around the information from a single source, they should be built around an idea.

-

What information is too much for the introduction?

Background information should only include material that is directly relevant to your research and fits into your story; it does not need to contain an entire history of the field of interest.

-

Do Not Use Nouns as Adjectives

Not: ATP Formation; reaction product

But: formation of ATP; product of the reaction

-

The Word “This”

“This” must always be followed by a noun, so that its reference is explicit.

- Not: This is a fast reaction; This leads us to conclude

- But: This reaction is fast; This observation leads us to conclude

-

Choosing Citations – Things to Look for

- A paper from a specialist journal written by a leader recognized as a strong writer (a good gauge is a very high # of times cited)

- A “normal” paper from a specialist journal

- A review or synthesis paper

- A paper from Nature or Science or some journal that targets a broad audience

- Avoid overly specific papers that focus on details that are not relevant to your topic (If you are studying monkey behavior, do not include a paper about an enzyme in that monkey that is not directly relevant to the behavior you are studying)

-

Voice

Avoid passive voice as much as possible. Write concise, active sentences.

Write in first-person. Instead of “This project will …” or “The author will …” write “My project will …” or “I will…”

-

Use of Outlines

Use outlines to develop flow and logical organization to your writing…

But always write in narrative. Do not use outlines in your writing and avoid use of bullet points in all but rare instances.

-

Avoid Dramatic and General Statements

Avoid general statements like “I found …” with a statement that simply says what you found “Cowbirds use their hosts …”

Try to avoid dramatic and general statements, especially in opening sentences. Avoid sentences with obvious or self-created importance like “Solving climate change is critically important” or “Very little is known about <<my specific issue>>”

Much of the content on this page is based on information in:

Turbek, S.P., T.M. Chock, K. Donahue, C.A. Havrilla, A.M., Oliverio, S.K. Polutchko, L.G. Shoemaker, and L. Vimercati. 2016. Scientific writing made easy: a step-by-step guide to undergraduate writing in the biological sciences. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 97:417-426.